by Steve Selden | May 11, 2017 | Conservation

President Donald Trump signs an order along with Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, right, on, April 28, 2017. The Executive Order gives the Interior Department directions to review restrictive drilling policies for the outer-continental shelf. Associated Press photo.

Alaska continues to fight to preserve the wild spaces that give the state its incredible natural character. A number of Alaska environmental and Native groups filed a lawsuit against the federal government challenging President Donald Trump’s executive order attempting to reverse regulations that restrict and ban oil and gas drilling, inland and offshore of Alaska’s Arctic.

Natural Resources Defense Council, Earthjustice, The League of Conservation Voters and other green agencies jointly filed the complaint in Alaska’s federal district court last week after Trump’s April 28th order, signed amid members of Alaska’s congressional delegation. The crux of the filing was that President Trump’s order exceeded authority under federal law.

Prior to the new administration taking office, then-President Barack Obama signed into law the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act designating areas of the Arctic and Atlantic oceans off limits to oil and gas drilling.

The contending environmental groups argue that Trump’s action is illegal since Obama’s enacted law doesn’t have a provision explicitly allowing the order to be reversed.

Trump’s “executive order attempting to undo President Obama’s historic protection of the Arctic and Atlantic oceans from drilling is part of a plan to sell off our oceans to polluting corporations at the cost of the safety of coastal communities, the fate of marine wildlife and our children’s future,” said Earthjustice president Trip Van Noppen.

“These areas have been permanently protected from the dangers of oil and gas development. President Trump may wish to undo that, and declare our coasts open for business to dirty energy companies, but he simply lacks the authority to do so under the law,” said Niel Lawrence, NRDC senior attorney.

Trump’s “executive order attempting to undo President Obama’s historic protection of the Arctic and Atlantic oceans from drilling is part of a plan to sell off our oceans to polluting corporations at the cost of the safety of coastal communities, the fate of marine wildlife and our children’s future,” said Earthjustice president Trip Van Noppen.

Many other entities are involved in the lawsuit including Alaska Wilderness League, Sierra Club, Greenpeace and the Wilderness Society along with a handful of smaller local groups.

In a statement released by The Arctic Energy Center, an oil industry affiliate, rationale behind the lawsuit was challenged.

“There’s no precedent to show a ban should be permanent, there is nothing to suggest a subsequent White House cannot overturn the decision, and that the last administration’s application of the rule conflicts with the act’s wider specification to ensure (the Outer Continental Shelf) is ‘available for expeditious and orderly development,’ ” stated spokesman Oliver Williams.

by Steve Selden | May 5, 2017 | Conservation

Polar bear habitat protection is becoming a hot issue. Daisy Gilardini photo.

The U.S. Supreme Court stood up against a coalition of organizations within Alaska by declining to hear a case on Monday which attempts to repeal the previous federal government administration’s policy to designate more than 187,000 square miles of Alaskan wilderness as critical habitat for threatened polar bears.

Lawsuits filed against the Interior Department by the Alaska Oil and Gas Association and the state of Alaska along with Native corporations and local governments were able to reverse the regulation in 2013 though the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals reversed that ruling.The state of Alaska and the Alaska Oil and Gas Association — joined by Native corporations and local governments — brought lawsuits against the Interior Department to overturn that decision.

However, the U.S. Supreme Court decided against hearing the case and therefore the ruling reverted back to the original law which was instituted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The area in Alaska’s Arctic was protected by the federal government in December 2010.

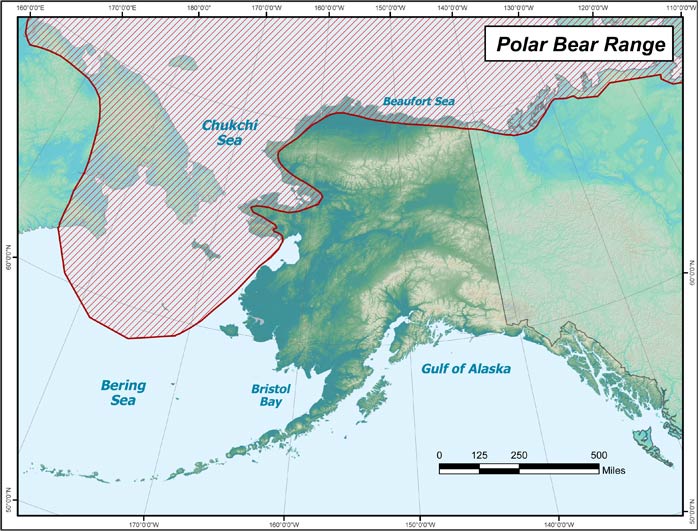

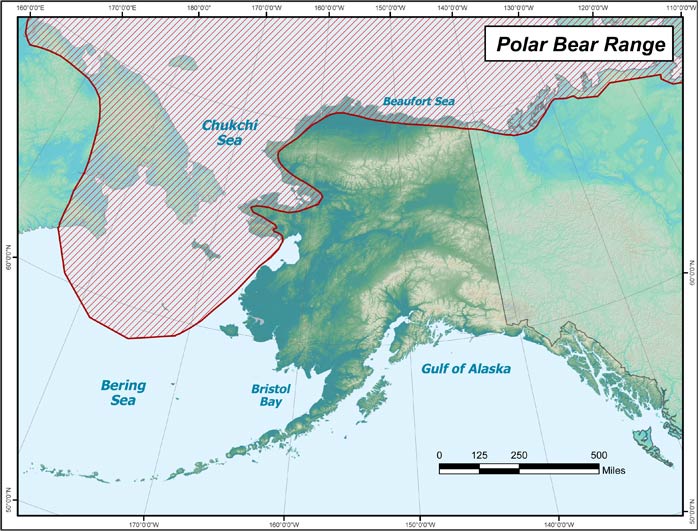

Alska polar bear habitat. State of Alaska photo.

Opposition groups filing appeals against the original designation claimed that the Fish and Wildlife Service overstepped its authority and created major economical consequences with relatively no conservation benefit whatsoever. The argument presented to the Supreme court attempted to overturn the decision by the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals which left Fish and Wildlife open to make “sweeping designations (in this case an area the size of California) that overlap with existing human development (including, even, industrial areas).” further arguing that the designated polar bear habitat interfered with oil industry operations as well as tribal sovereignty.

Mother polar bears avoid having their cubs swim in the ocean until they have the fat reserves to protect them. Jonathan Hayward photo.

“Swept within that enormous block of land are the entire ancestral homelands for certain Native communities, as well as the largest and most productive oil field in North America,” the petition to the oil and gas group gave the Supreme Court. Nearly 96 percent of the protected habitat area is sea ice, the smaller, remaining area includes “industrial facilities, garbage dumps, airports, communities, and homes (from which bears are actively chased away) as ‘critical’ habitat that is purportedly free from ‘human disturbance’ or otherwise ‘unobstructed,’ ” the petition said.

The coalition of various groups argued further that the 9th Circuit Court’s broad ruling would allow for expansion of habitat designations in other regions of the United States.

The government stated that it utilized two rounds of public comment and current, leading scientific data in defense of why the protected habitat was designated by courts initially.

“The Service did not designate any areas outside the geographical area currently occupied by polar bears because it determined that ‘occupied areas are sufficient for the conservation of polar bears in the United States,’ ” the federal government reported to the Supreme Court.