Let’s face it, “cold” is what the Arctic does best….especially to those living below this amazing region of our planet Earth. So, other than the hearty mammals, particularly the mighty polar bear and humans, very few birds overwinter at high latitudes. Less than 10% of all birds that venture to Arctic and sub-Arctic regions unpack their bags and set up a permanent home there.

Birds that do either have some hearty DNA or have developed some unique ways to cope with cold temperatures that can dip to -55 Celsius. Most of you know the raven can subsist just about anywhere on the planet and the intelligence and intuitiveness of this creature has been well documented. He is truly the sentinel of true survival…especially as his shining black defiantly glares out against the snowy north.

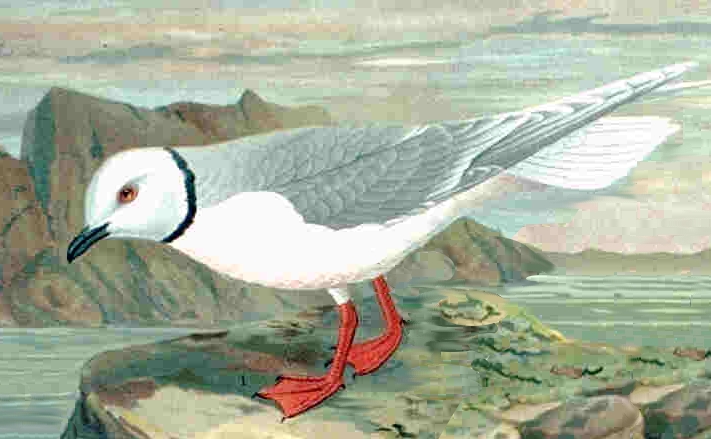

Rock and willow ptarmigan can be seen in Churchill as the fall arrives and throughout the winter, changing to their winter’s best camouflage white. Ivory and the illusive and highly prized Ross’s gull also stay put for the winter. I’ve spotted the Ross three times in over a decade of guiding Natural Habitat Churchill summer trip. All three times the sightings were facilitated by Churchill birding master and legend Bonnie Chartier when we worked together up north.

The Common and hoary redpoll, Brunnich’s Guillemot, Little Auk and Black Guillemot also inhabit the Arctic full-time. Snow buntings and gray jays are quite friendly species that call Churchill home all year. Higher up in Greenland the birds tend to shelter in utility tunnels known as utilidors.

Boreal chickadees and occasionally boreal owls and great horned owls inhabit the boreal forest. And, the mighty gyrfalcon, the fourth fastest bird on the planet…er off the planet, can be seen sporadically hunting or soaring from point to point. I have seen this bird dart across the Churchill tundra and even through town.

The most intuitive behavior exhibited for warmth and survival is how ptarmigan and common hoary redpolls take shelter in snowdrifts and endure the frigid cold by utilizing the snow as insulation. Ptarmigan and Snowy Owls grow leg and feet feathers to keep them warm throughout the winter months. They also change plumage from dark to white in order to stay camouflaged and safe from predators.

The summer months are reminiscent to a beach-side resort with the bird population ballooning by more than 200 additional migrant species arriving in early spring. These are birds that cannot survive the harsh conditions of winter in the far north though return each year to take advantage of the bounty of food sources thriving in the Arctic summer. The most incredible journey is clearly that of the Arctic tern…making the pole to pole round trip of nearly 45,000 miles.

Many of these species arrive early and set up nests for the short but productive breeding season. With snow cover still prevalent, these hearty nurturing parents live off their stored fat reserves for energy. The majority of the Arctic and sub-Arctic species are wetland feeders such as various ducks, swans and geese. Waders and shorebirds also scour the marshes and shoreline plucking all the organisms they can from the Earth.